The Sweeper is a classic ghost story written by A.M. Burrage. It’s about an old woman who lives in fear of Autumn and the dead leaves falling from the trees.

Tessa Winyard thought that it was strange that Miss Ludgate was kind to beggars. For there was a thin streak of stinginess in her. Miss Ludgate was rich enough not to care what others thought. But she was old enough to be crotchety.

Miss Ludgate gave little to local charities. Yet she was very generous in her charity to individ-uals. Her neighbors were not grateful to her for this. They said that she encouraged every strange character who passed that way.

Tessa Winyard first agreed to work as a com-panion for Miss Ludgate on a month’s trial. She knew that Miss Ludgate would be difficult. She did not know whether she would be able to keep he job—or if she would want to keep it. Tessa had found the job because she knew a niece of he old lady. The niece was able to give Tessa hints about her aunt’s behavior.

When Tessa entered the house for the first time, she fell under the spell of it. She loved old country mansions. The house was called Billingdon Abbots. It was very old. The gardens around the house had many trees. They gave the house an air of melancholy.

At first, the interior of the house filled Tessa with awe. She loved pretty things. But she was afraid of furniture and pictures that were so coldly beautiful.

Tessa spent most of her time with Miss Ludgate in the drawing room. There were homelier -looms that held photographs of living people. But Miss Ludgate preferred to sit in the draw-ing room near the cabinet of priceless china,- It was as if she realized that she was only the guardian of her treasures. She wanted to have them within sight now that her term of guardianship was drawing to a close.

Miss Ludgate must be over 80, Tessa thought. She was very small and frail. Winter and summer, she wore a white shawl inside the house. In summer, she wore a lighter-weight shawl. It matched her hair in color. Her eyes were blue and piercing. Her once-beautiful mouth looked grim. She always spoke very slowly. Since she knew that she had only to be understood to be obeyed, she made sure that she was understood.

Tessa spent her first week with Miss Ludgate without knowing whether or not she liked the old lady. She had no idea how Miss Ludgate felt about her. Tessa did what she was told and thought before she spoke. But she wondered what place she was to fill.

The truth is that Miss Ludgate wanted to we somebody young around the house. The ser-vants were old family servants. They remained faithful to her because of rumors of legacies. She was lonely and starved for companionship.

Tessa was able to play the piano well. So was Miss Ludgate, until her fingers stiffened with rheumatism. Now the piano was no longer silent. Miss Ludgate regained an old lost pleasure. Tessa was 22. She was not a beauty. Her good looks were the result of perfect health and her youth.

When Tessa had been with Miss Ludgate a week. the old lady called her “Tessa” for the first time. She added, “I hope you intend to stay with me, my dear. It will be dull for you, and you may find me a bother. But I will not take up all your time. I think that you will be able to find friends and amusements.

So Tessa stayed on beyond the first month. A friendship existed between the two women. At times, they were able to touch hands over the barrier between youth and age. Tessa felt tenderness toward Miss Ludgate. She reminded Tessa of a poor actress who played the part of a queen. She wore cheap crown jewels and gave commands which other actors obeyed. The realities of life — wet streets, poor meals, and cold rooms — waited for her when the curtain fell.

Tessa was filled with pity when she thought how short a time Miss Ludgate had to live. She wondered how it must feel to think every evening of a tomorrow that might not be.

Tessa would have found life dull except for the complete change in her surroundings. She was the daughter of a country minister, one of seven brothers and sisters. They had worn one another’s clothes, worn out carpets, and mishandled furniture. They had broken everything but their parents’ hearts. The grandeur of living with Miss Ludgate broke the monotony for Tessa.

She wrote a letter home to her mother: “This house might have come out of a book in which there is a mystery. There is no mystery that I have heard of. But at least it ought to have a ghost. I don’t like to ask Miss Ludgate. She might believe in ghosts, and it might scare her to talk about them. Or she might not. Then she would be furious with me for talking about them. But we are certainly haunted by tramps.”

Her letter went on to describe the daily visits of those who beg and steal on their way from workhouse to workhouse. Three or four of them showed up each day. None went away empty-handed. Mrs. Finch, the housekeeper, had orders and she carried them out. When there was no spare food, she gave them money.

Tessa was always meeting these vagrants on the path. She grew used to them. They knew she only worked there and could be fired. But they knew that they were always welcome guests. Tessa resented their presence. She secretly raged against Miss Ludgate for encouraging them.

The girl knew about the struggles of the decent poor. Her upbringing had taught her about the poverty of farmhands and laborers. On Miss Ludgate’s estate, some families lived on bread and potatoes. Yet the old lady had no sympathy for them and gave everything to beggars.

Tessa could not speak to Miss Ludgate about the subject. If she did, she might lose her job. But she did mention it to Mrs. Finch. At first, Mrs. Finch said only one word — “Orders!” After a moment, she added. “Miss Ludgate has her own good reasons for doing this — or thinks she has.”

It was late summer when Tessa first moved to the estate. She looked at the trees from her window every morning. And she watched the progress of the year. The yellow leaves began to give way to gold and brown and red.

One evening, Miss Ludgate appeared in her winter shawl. She seemed depressed. As she sat at the table, she leaned on her elbows and rested her face between her hands.

“Are you well, Miss Ludgate?” Tessa asked.

“My bad time of the year is approaching,” the old woman replied. “If I can live until the end of November, I will last another year. But I don’t know yet.”

“Of course you’re not going to die this year,” Tessa said in a voice that would soothe a child.

“If I don’t die this autumn, it will be the next.” The old voice quavered. “It will be in the autumn that I will die. I know that.”

“But how can you know,” Tessa asked gently.

“It does not matter how I know. Have many leaves fallen yet?”

“Hardly any,” said Tessa. “There has been very little wind.”

“They will fall very soon now,” said Miss Ludgate.

Two days later, it rained heavily. The wind sprang up. Showers of yellow leaves fell to earth. Miss Ludgate sat watching them. During dinner. the wind and the rain stopped. Tessa peeped between the blinds. It looked as though it was going to be a fine night. Miss Ludgate got out a deck of cards. Tessa picked up a book. There was silence except for the sound of the cards being placed on the polished table.

Tessa could not have said when she first heard it. But gradually she had become aware of sounds in the garden outside. Finally. she was forced to wonder what caused them. She could not guess how long they had been going on.

Tessa closed the book and listened. The sounds were crisp, dry, and drawn out. There was a pause after each one. What was it? Then Tessa knew. On the long path behind the building, somebody was sweeping up leaves with a broom. But what a time to sweep up leaves! She continued to listen. She was sure that was the sound. But she could not imagine any gardener working at this hour. She looked at Miss Ludgate, but she said nothing.

Miss Ludgate sat listening. Her face was half-turned toward the window. It was dreadful to see someone who was so old be so tense. Tessa not only listened, she now watched.

There was a movement in the silent room. Miss Ludgate had turned her head. Tessa knew that Miss Ludgate had caught her listening to the sounds from the path outside. For some reason the old lady was annoyed with Tessa for hearing them. But why? And why was there a look of terror on the poor old face?

“Will you play something on the piano, Tessa?”

Although it was a question, Tessa knew it was a command. She was to drown out the noise of the sweeping from outside. So Tessa played songs that allowed her to use the loud pedal. After half an hour, Miss Ludgate stood up. She gathered her shawl around her shoulders and hobbled to the door. She stopped on the way to say good night to Tessa.

Tessa began to play softly. The sound of sweeping from the path outside had stopped now. Was Miss Ludgate ashamed because she had a gardener at work at this hour? And why was Miss Ludgate so terrified? Did it have anything to do with her belief that she would die in the autumn?

The night was calm. Many more leaves will not fall tonight. Tessa thought. But the next morning when Tessa walked out into the garden, the lung path was thickly covered with them. Toy, one of the gardeners. was sweeping them with a broom.

“Hello,” said Tessa. “A lot of leaves fell last night.”

Toy stopped sweeping and shook his head. “No. This little bunch came down with the wind in the early part of the evening.”

“But they were all swept up. I heard somebody at work here after nine. Was it you?”

The man grinned. “You will never catch any of us at work after nine o’clock,” he said. “Nobody has touched them until now. As soon as you sweep them up, more are waiting. At this time of year, 100 men could not keep this garden tidy.”

That night, Miss Ludgate went to bed early. Tessa went into the drawing room to pick up her book. She had taken only two steps into the room when she stopped and stood listening. It was now nine-thirty. In spite of what Toy Lad told her, somebody was sweeping the path. She tiptoed to the windou and peeped out between the blinds. She could have walked out the door and into the garden, but she felt that she would rather see the mysterious worker — for the first time — from a distance.

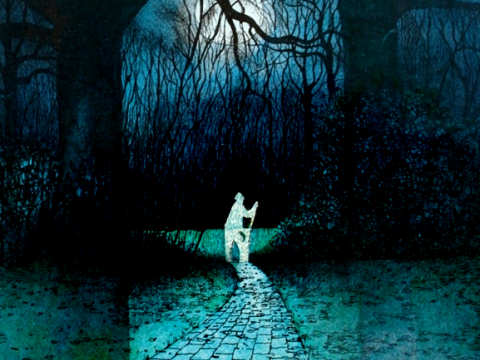

Then Tessa remembered that there was a window on the upstairs landing. She walked upstairs on tiptoe. Through the window, the moonlight threw a pale blue screen on the opposite wall. Tessa raised the window softly and silently, and leaned out.

On the path below her, a man was slowly sweeping with a stable broom. The broom swung and struck the path with a soft, crisp swish. The strokes were as regular as those of the pendulum of some slow clock. Tessa was unable to see most of the features of the figure underneath the window. It was a workman who seemed to be wearing old and baggy clothes. But there was something odd about the whole scene. She knew that there was something missing. Yet she could not say what it was. Suddenly she felt sick and dizzy. She stepped away from the window.

The coward in Tessa urged her to go to bed and forget what she had seen. But the Tessa who despised cowards urged her to have cour-age. She said to herself. “Go down and see who it is and what’s wrong with him.”

Tessa walked downstairs again. She unlocked the door and stepped into the moonlight. The Sweeper was still at work where the path ended and a gate led to the stable yard. The girl saw that he was not making progress with his work. The broom rose and fell, but the dead leaves remained beneath it. This was not what she had noticed. Something was still missing.

Her footsteps made only a light noise on the path, but the Sweeper heard them while she was still half a dozen yards away from him. He turned and looked at her. He was a tall man with the face of a corpse. His eyes bulged like huge rising bubbles. It was a foul, suffering face that could make you feel disgust or horror, but never pity. He was dressed in rags. The hands that grasped the broom seemed to be only skin and bones. He was so thin that Tessa thought he was almost transparent. She was sickened by the thought.

They faced each other for a fraction of eternity. Then Tessa screamed. She suddenly realized the something that was missing. The path was flooded with moonlight, but the visitor had no shadow. She saw dimly through the figure that the ivy was moving upon the wall. As her mind raced to tell her that the Thing was evil, she was left suddenly and dreadfully alone. The spot where the Thing had stood was empty except for the moonlight and the litter of leaves.

The next thing that Tessa remembered was being in the hall, faint and sobbing. She saw a light on the wall above and wondered if she was going to meet another horror. But it was only Mrs. Finch walking with a candle in her hand.

“What is the matter, Miss Tessa? Have you been outside?”

Tessa sobbed and tried to speak. “I have seen—”

Mrs. Finch put her arm around the shivering girl. “Hush, my dear. I know what you have seen. You should not have gone out. I have seen it, too, but only once.”

“What is it?”

“Now don’t be frightened. He doesn’t come for you. It’s Miss Ludgate that he wants. You have nothing to fear. Where was he when you saw him?”

“He was close to the end of the path near the stable gate.”

Miss Finch threw up her hands. “Oh, poor Miss Ludgate. Her time is growing short. The end is near now.”

“I must know,” Tessa sobbed. “Tell me.”

“Come into my parlor, and I’ll make a cup of tea. But you should not know tonight.”

“I must, if I am to have any peace.”

The fire was still burning in Mrs. Finch’s parlor. In a few minutes, the tea was ready. Tessa took a sip and felt her courage returning.

“I’ll tell you, Miss Tessa.” said the old housekeeper. “But don’t let Miss Ludgate know I’ve told you.”

Tessa nodded.

“Miss Ludgate did not always give to beggars — not until about 15 years ago. She was old then, but active. She was fond of gardening. Late one afternoon while she was cutting some roses, a beggar came to the side door. He was sick and starved. But you have seen him. I felt sorry for him. I was just going to risk giving him some food when Miss Ludgate walked up.

‘What is this?’ she asked. ‘He whined about not being able to get work,’ I told her. ‘Work!’ said Miss Ludgate. ‘You don’t want work. You come here looking for a hand-out. If you want to eat, you will have to work first. There is a broom and there is a path covered with leaves. Start sweeping at the top. When you come to the end, you can come and see me.’

“He took the broom. A feu minutes later. I heard Miss Ludgate shout. I hurried out. The man was lying at the top of the path where he had started sweeping. He had collapsed and fallen. I didn’t know then that he was dying. He gave Miss Ludgate a look that I cannot forget. ‘When I have swept to the end of the path,’ he said, ‘I’ll be back for you, my lady. We will feast together. Just make sure that you are ready when I get there.’

Those were his last words. He was buried by the parish. It upset Miss Ludgate so much that she ordered something to be given to every beggar. Not one of them is to be asked to do a stroke of work. But the next autumn, he came back and started sweeping right at the top of the path where he had died. We have all heard him, and most of us have seen him. Year after year, he has swept with his broom. It makes a brushing noise. and it hardly moves a leaf. But when he gets to the end — well, I would not like to be Miss Ludgate with all her money.”

Three evenings later, just before the hour for dinner. the Sweeper completed his task. That is to say, if we believe Mrs. Finch’s story. The servants heard somebody burst open the side door. Two of them rushed into the hall. They saw that the door was open, but no one was there. Miss Ludgate was already in the drawing room. Tessa was still upstairs dressing for dinner. At that moment, Mrs. Finch walked into the drawing room to speak to Miss Ludgate.

Mrs. Finch’s screams warned the household of what had happened. Tessa heard them just as she was ready to go downstairs. She rushed into the drawing room. Miss Ludgate was sitting in her favorite chair. Her eyes were open but she was dead. Her eyes here filled with a terror that Tessa could not bear to see.

When Tessa stopped staring at Miss Ludgate, she saw something on the carpet. She bent down to pick it up. It was a little yellow leaf. She did not ask how it got there. She dropped it, shuddering. It looked as if it had been picked up by, and later fallen from, the birch twigs of a stable broom.

Spoopy! :3

That was a wonderful story!!!! I really liked it.

This shows the importance of being kind to less fortunate.The man had his revenge.