The Pipe-Smoker is a creepy short story by Martin Armstrong about a man who gets caught in a storm and seeks refuge at the lonely house of a recluse. As he waits for the storm to break, the man listens to the tale the recluse tells of how he came to be in such a lonely place.

I don’t usually mind walking in the rain, but on this occasion the rain was coming down in torrents and I had still ten miles to go. That was why I stopped at the first house, a house about a mile from the village ahead of me, and looked over the garden gate.

The house didn’t look promising, for I saw at once that it was empty. All the windows were shut, and not one of them had a blind or a curtain. Through one on the ground floor I saw bare walls, a bare mantelpiece, and an empty grate. The garden too was wild, the beds full of weeds; you would hardly have known it for a garden but for the fence, the vestiges of straight paths, and the lilac bushes which were in full bloom and sent showers of water to the grass every time the wind tossed them.

You can imagine, then, that I was surprised when a man strolled out from the lilacs and came slowly toward me down the path. What was surprising was not merely that he was there, but that he was strolling aimlessly about, bareheaded and without a mackintosh, in the drenching rain. He was rather a fat man and dressed as a clergyman, gray-haired, bald, cleanshaven, with that swollen-headed and over-intense look which one sees in portraits of William Blake. I noticed at once how his arms hung limply at his sides. His clothes and – what made him still stranger – his face were streaming with water! He didn’t seem to be in the least aware of the rain. But I was. It was beginning to trickle through my hair and down my neck, and I said: “Excuse me, sir, but may I come in and shelter?”

He started and raised puzzled eyes to mine. “Shelter?” he said.

“Yes,” I replied, “from the rain.”

“Ah, from the rain. Yes, sir, by all means. Pray come in.”

I opened the garden gate and followed him down a path toward the front door, where he stood aside with a slight bow to let me pass in first.

“I fear you won’t find it very comfortable,” he said when we were in the hall. “However, come in, sir; in here, first door on the left.”

The room, which was a large one with a bow window divided into five lights, was empty, except for a deal table and bench and a smaller table in a corner near the door with an unlighted lamp on it.

“Pray sit down, sir,” he said, pointing to the bench with another slight bow. There was an old-fashioned politeness in his manner and language. He himself did not sit down, but walked to the window and stood looking out at the streaming garden, his arms still hanging idly at his sides.

“Apparently you don’t mind rain as much as I do, sir,” I said, in an attempt to be amiable.

He turned around, and I had the impression that he could not turn his head and so had to turn his whole body in order to look at me.

“No, no, no!” he replied. “Not at all. In point of fact, I hadn’t observed it till you pointed it out.”

“But you must be very wet,” I said. “Wouldn’t it be wiser to change?”

“To change?” His gaze became searching and suspicious at the question.

“To change your wet clothes.”

“Change my clothes?” he said. “Oh, no! Oh, dear me, no, sir! If they’re wet, doubtless they’ll dry in course of time. It isn’t raining in here, I take it?”

I looked at his face. He really was asking for information.

“No,” I replied, “it isn’t raining in here, thank goodness.”

“I fear I can’t offer you anything,” he said politely. “A woman comes from the village in the morning and evening, but meanwhile I’m quite helpless.” He opened and closed his hanging hands. “Unless,” he added, “you would care to go to the kitchen and make yourself a cup of tea, if you understand such things.”

I refused, but asked leave to smoke a cigarette.

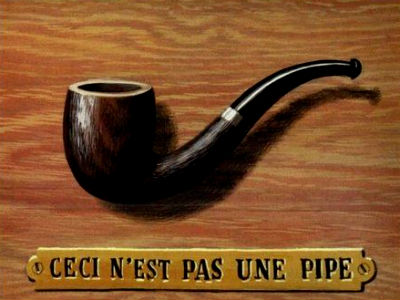

“Pray do,” he said. “I fear I have none to offer you. The other, my predecessor, used to smoke cigarettes, but I’m a pipe-smoker.” He brought a pipe and pouch from his pocket: it was a relief to see him use his arms and hands.

When we had both lit up, I spoke again: I was conscious all the while that the responsibility for conversation was mine; that, if I had not spoken, my strange host would have made no attempt to break the silence, but would have stood with his arms at his sides looking straight in front of him either at the garden or at me. I glanced round the bare room.

“You’re just moving in, I suppose?” I said.

“Moving in?” He shifted slightly and turned. his intense, uncomfortable gaze on me again.

“Moving into this house, I mean.”

“Oh, no,” he said. “Oh, dear me, no, sir. I’ve been here for several years; or rather, I myself have been here for nearly a year, and the other, my predecessor, was here for five years before that. Yes, it must be seven months now since he passed away. No doubt, sir” – a melancholy, wistful smile unexpectedly transformed his face – “no doubt you won’t believe me – Mrs. Bellows wouldn’t – when I tell you I’ve been here only seven months, there or thereabouts.”

“If you say so, sir,” I replied, “why should I disbelieve you?”

He took a few steps toward me and lifted his right hand. Reluctantly I took it, a thick, limp, cold hand that gave me an unpleasant thrill.

“Thank you, sir,” he said, “thank you. You’re the first, absolutely the first…!”

I dropped the hand and he did not finish the phrase. He had fallen, apparently, into a reverie. Then he began again.

“No doubt all would have been well if only my – that is, my predecessor’s old cousin had not left him this house. He was better off where he was. He was a clergyman, you know.” He opened his hands, exhibiting himself. “These are his clothes.” Again he absented himself, fell into a reverie, while his body in its clergyman’s clothes stood before me. Suddenly he asked me, “Do you believe in confession?”

“In confession?” I said. “You mean in the religious sense of the term?”

He took a step closer. He was almost touching me now. “What I mean is,” he said, lowering his voice and looking at me intensely, “do you believe that to confess, to confess a sin or a – a crime, brings relief?”

What was he going to tell me? I should have liked to say no, to discourage any confession from the poor old creature, but he had put his question so appealingly that I could not find it in my heart to repulse him.

“Yes,” I said, “I think that by speaking of it one can often rid oneself of a weight on the mind.”

“You have been so sympathetic, sir,” he said with one of his polite bows, “that I feel tempted to trespass…!” He lifted one of his heavy hands in a perfunctory gesture and dropped it again. “Would you have the patience to listen?”

He stood beside me as if he had been a tailor’s dummy that had been placed there. His leg touched my knee. I felt strongly repelled by his closeness.

“Won’t you sit down there?” I said, pointing to the other end of the bench on which I was sitting. “I should find it easier to listen.”

He turned his body and gazed earnestly at the bench, then sat down on it, facing me, a leg on either side of it, leaning toward me. He was about to speak, but he checked himself and glanced at the window and the door. Then he took his pipe from his mouth and laid it on the table, and his eyes returned to me.

“My secret, my terrible secret,” he said, “is that I’m a murderer.”

His statement horrified me, as well it might; and yet, I think, it hardly surprised me. His extreme strangeness had prepared me, to some extent, for something rather grim. I caught my breath and stared at him, and he, with horror in his eyes, stared back at me. He seemed to be waiting for me to speak, but at first I could not speak. What, in the name of sanity, could I say? What I did say at last was something fantastically inadequate.

“And this,” I said, “weighs on your mind?”

“It haunts me,” he said, suddenly clenching his heavy, limp hands that lay on the bench in front of him. “Would you have the patience-?”

I nodded. “Tell me about it,” I said.

“If it hadn’t been for the legacy of this house,” he began, “nothing would have happened. The other, my predecessor, would have stayed in his rectory, and I… I should never have come on the scene at all. Although it must be confessed that he, my predecessor, was not happy in his rectory. He met with unfriendliness, suspicion. That was why he first came to this house… just as a trial, you see. It was bequeathed to him empty: simply the house-no furniture, no money… and he came and put in one or two things… this table, this bench, a few kitchen things, a folding bed upstairs. He wanted, you see, to try it, first. Its remoteness appealed to him, but he wanted to be sure about it in other ways. Some houses, you see, are safe, and some are not, and he wanted to make sure that this was a safe house before moving into it.” He paused and then said very earnestly, “Let me advise you, my friend, always to do that when you contemplate moving into a strange house… because some houses are very unsafe.”

I nodded. “Quite so!” I said. “Damp walls, bad drainage, and so on.”

He shook his head. “No,” he said, “not that. Something much more serious than that. I mean the spirit of the house. Don’t you feel” – his gaze grew more piercing than ever – “that this is a dangerous house?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Empty houses are always a little queer,” I said.

He reflected on this statement.

“And you have noticed,” he inquired at last, “the queerness of this one?”

I did, as he asked me the question, feel that the house was queer; but it was his queerness, I knew well enough, and the grim suggestiveness of his talk, that made it so, and I replied, “Not queerer than other empty houses, sir.”

He gazed at me incredulously. “Strange!” he said. “Strange that you shouldn’t feel it. Though it’s true that – that the other, my predecessor, didn’t feel it at first. Even this room – for this room, sir, is the dangerous room – didn’t seem strange to him at first; no, even in spite of a very peculiar thing about it.”

If it had been fine, I should have ended the conversation and left him, for the old man’s talk and manner were making me feel more and more uncomfortable. But it was not fine: it was raining as hard as ever and was becoming very dark. Evidently we were in for a thunderstorm.

The old man got up from the bench. “I think I can show you, now,” he said, “the peculiar thing about the room. It is visible only after dark, but I think it is dark enough now.”

He went to the little table in the corner and began to light the lamp. When it was alight and he had replaced the frosted glass globe, he brought it to the larger table and set it down to my left.

“Now,” he said, “sit square to the table.”

I did so. Before me across the bare room was the curtainless five-lighted bow window. “You are sitting now,” he said, laying a heavy hand on my shoulder, “where the other, my predecessor, used to sit and take his meals.”

I could not restrain a start, nor resist the impulse to turn and face him. It made me uneasy, to have him standing over me, behind me, out of sight. He appeared surprised.

“Pray don’t be alarmed, sir,” he said, “but turn back and tell me what you see.”

I obeyed. “I see the window,” I said.

“Is that all?” he asked.

I stared at the window. “No,” I said. “I also see five reflections of myself, one in each light of the window.”

“Just so,” said the old man, “just so! That is what the other saw when he took his meals alone. He saw the five other selves each eating its lonely meal. When he poured out some water, each of them poured out water: when he lit a cigarette, each of them lit a cigarette.”

“Of course,” I said. “And that alarmed your friend, the clergyman?”

“The Reverend James Baxter,” said the old man; “that was his name. Be sure not to forget it, my friend; and if people ask you who lives here, remember to say the Reverend James Baxter. Nobody knows, you see, that… that…!”

“Nobody knows what you told me. I understand.”

“Exactly!” he said, suddenly dropping his voice. “Nobody knows. Not a soul. You’re the first person I’ve mentioned it to.”

“And you’ve had no inquiries?” I asked. “This Mr. Baxter was not missed?”

He shook his head. “No,” he said. “Even Mrs. Bellows, who looked after him from the start, is not aware of what happened.”

I turned round and faced him incredulously. “Not aware, you mean to say-?”

“Not aware that I’m not he. You see,” he explained, “we were very much alike. Quite remarkably so! I can show you a photograph of him before you go and you’ll see for yourself.”

I now decided that, rain or no rain, I would go; there did not seem much reason, beyond the rain, for my staying. I stood up. “Well, sir,” I said, “I can only hope that you will feel the benefit of having relieved your mind of your-secret.

The old gentleman became very much agitated. He clasped and unclasped his two limp hands. “Oh, but you must not go yet. You haven’t heard half of it. You haven’t heard how it happened. I had hoped, sir – you have been so kind – that you’d have the patience and the kindness to…!”

I sat down again on the bench. “By all means,” I said, “if you have more to say.”

“I had just told you, hadn’t I?” the old gentleman went on, “that I – that the other – that my predecessor used to sit here at his meals and see his five other selves mimicking him? When he lit his cigarette he saw five other cigarettes lighted simultaneously…!”

“Naturally,” I said.

“Yes, naturally,” said the old boy; “it was all perfectly natural, as you say; perfectly natural till one night, one terrible night.” He stopped and stared at me with horror in his eyes.

“And then?” I said.

“Then a strange, a dreadful thing happened. When he, my predecessor, had lit his cigarette, watching those other selves, as he always did, he saw that one of them, the one on the extreme left, had lit, not a cigarette, but a pipe.”

I burst out laughing. “Oh, come, come, sir!”

The old man wrung his hands in agitation. “It is comic, I know,” he said, “but it is also terrible. What would you have thought if you had actually seen it yourself? Wouldn’t you have been appalled?”

“Yes,” I said, “if it had actually happened. If I had really seen such a thing, of course I should.”

“Well,” said the old fellow, “it did happen. There was no possible mistake about it. It was appalling, ghastly.” There was as much horror in his voice as if he had actually seen the thing himself.

“But, my dear sir,” I said to him, “you have only the word of this Mr. – Mr. Baxter for it.”

He stared at me, his eyes blazing with conviction. “I know it happened,” he said; “I know it much more certainly than if I had seen it. Listen. The thing went on for five days: on five successive evenings my predecessor watched in horror for the thing to right itself.”

“But why didn’t he go – leave the house?” I asked.

“He daren’t,” said the old man in a strained whisper. “He daren’t go: he had to stay and see for certain that the thing had righted itself.”

“And it didn’t?”

“On the sixth night,” said the old man with bated breath, “the fifth reflection, the one that had broken away from obedience, had gone.”

“Gone?”

“Yes, gone from the window. My predecessor sat gazing in terror at the blank pane and the other four stared back in terror into this room. He glanced from the empty pane to them and they stared back at him, or at something behind him, with horror in their eyes. Then he began to choke – to choke,” gasped the old man, himself almost choking, “to choke, because hands were round his throat, clutching, throttling him.”

“You mean that the hands were the hands of the fifth?” I asked, and it was only my horror at the old man’s horror that prevented my smiling cynically.

“Yes,” he hissed, and he held out his thick, heavy bands, gazing at me with staring eyes. “Yes. My hands!”

For the first time I was really terrified. We stared speechless at one another, he still gasping and wheezing. Then, hoping to soothe him, I said as calmly as I could, “I see. So you were the fifth reflection?”

He pointed to his pipe on the table. “Yes,” he gasped; “I, the pipe-smoker.”

I stood up. My impulse was to hurry to the door. But some scruple held me there still, a feeling that it would be inhuman to leave him alone, a prey to his horrible fantasy; and, with a vage idea of bringing him to his senses, of easing his tortured mind, I asked, “And what did you do with the body?”

He caught his breath, a shudder distorted his face, and, clenching his two extended hands, he began to beat his breast convulsively.

“This,” he shouted in a voice of agony, “this is the body.”

Add comment